Climate disasters cost billions. What is Central Kentucky's plan?

The Central Kentucky Climate Action Plan combines the efforts of urban and rural municipalities to push for climate action.

The Central Kentucky Climate Action Plan combines the efforts of urban and rural municipalities to push for climate action.

This story was produced as part of a joint Equitable Cities Reporting Fellowship for Rural-Urban Issues between CivicLex and Next City.

Two myths tend to shape how people talk about Kentucky and climate change. One is that the state is a “climate haven,” insulated from the worst effects of global warming. The other is that Kentuckians are hostile to climate action.

Officials pushing for change – researchers, environmental directors, and more – say their conversations around climate are more nuanced than a red or blue ticket makes it look.

Kentucky is the sixth-most climate-vulnerable state, according to a report by Texas A&M University and the nonprofit Environmental Defense Fund. From 2020 to 2024, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration documented 27 “billion-dollar” climate disasters in the state, including tornadoes that killed more than 50 people in western Kentucky and flash floods that killed 39 in the east.

From the outside, the Commonwealth’s politicians and residents – largely rural, with a reputation for voting conservative – may appear indifferent. Last year, state leaders passed S.B. 89, removing groundwater and wetland protections, and stood by President Donald Trump as he signed executive orders to boost the coal industry.

“I am delighted to share that that is a false assumption. And absolutely, it is an assumption that people make,” says Lauren Cagle, a professor at the University of Kentucky specializing in climate rhetoric.

Locally, municipalities varying in population density, income levels, and industry are teaming up to strengthen their own communities’ climate resilience through a six-county regional climate action plan. The draft Central Kentucky Climate Action Plan, published last fall through an Environmental Protection Agency grant, targets an area of more than half a million people. Their leaders say neither politics nor an urban-rural divide can predict the popularity and effectiveness of climate action.

“There are three parts to this, and it includes the environment, the people, and the economy. We believe if we focus on those three areas, then we can make our community stronger,” Jada Walker Griggs, the senior program manager in sustainability for Lexington-Fayette Urban City Government (LFUCG), explains.

Under the plan, the six counties – Bourbon, Clark, Fayette, Jessamine, Scott and Woodford — as well as municipal governments within will collaborate to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 23% by 2035 and 40% by 2050, as compared to 2021 levels.

“Since the early '90s, we have seen this attempt to pit local and global versus each other. We've seen this attempt to pit individual choice versus systemic change against each other. And we've seen this attempt to pit urban versus rural. And these are all false choices,” says Cagle, who has closely followed the climate action plan’s development.

Regardless of federal and state action, the region is prioritizing initiatives that push actions countering and mitigating climate change. After all, Lexington aims to be carbon neutral by 2050.

Since 2004, the Lexington-Fayette Urban County Government has implemented an energy management plan to reduce consumption of fuel, and leaders commissioned a greenhouse gas inventory in 2021. They had already published a sustainability plan as far back as 2012 under Empower Lexington.

But in 2023, when officials searched for implementation grants, they realized more funding would be accessible if they included the entire Lexington Metropolitan Statistical Area.

“That's not only Fayette County,” Griggs said. “That's Clark County, and Scott and Bourbon and Jessamine and Woodford Counties, and then their municipal governments.”

Fayette County fared better than most of the Commonwealth in Texas A&M’s report, scoring in the 58th percentile for climate vulnerability: While it doesn’t experience many extreme weather events, the area’s environmental factors like land use and pollution dragged down its score. Nearby Clark County ranked in the 91st percentile nationwide, and Bourbon County ranked 96th. The contrast between those counties, according to the report, is largely due to infrastructure differences and residents’ physical health.

The Central Kentucky Climate Action Plan, which shows how these governments can work in tandem to reduce harmful emissions, is funded by a $1 million EPA grant. It’s a collection of two documents.

The Priority Climate Action Plan provides quick, high-impact changes for central Kentucky communities to adopt, including plans for:

The Comprehensive Climate Action Plan offers a more thorough analysis for long-term growth, based on detailed data about each county’s vulnerabilities, economics and how their emissions and goals vary by region and demographic. Its recommendations include:

Griggs explains it’s vital that people across the region understand the very basics of climate change and pollution, as well as why these actions help. That’s part of why the Climate Action Plan has gone through multiple rounds of community input, from public focus group gatherings to community ambassadors.

When Cagle attended one of these focus groups in Lexington, she was amazed at how many passionate people showed up.

“It was [so] packed, we had to bring chairs in. People were showing up to participate. In that room of however many people, everybody was excited about this vision,” Cagle says. “There was one person there who [voiced skepticism] about the reality of anthropogenic climate change, but was also willing to have a conversation about the vision for the future.”

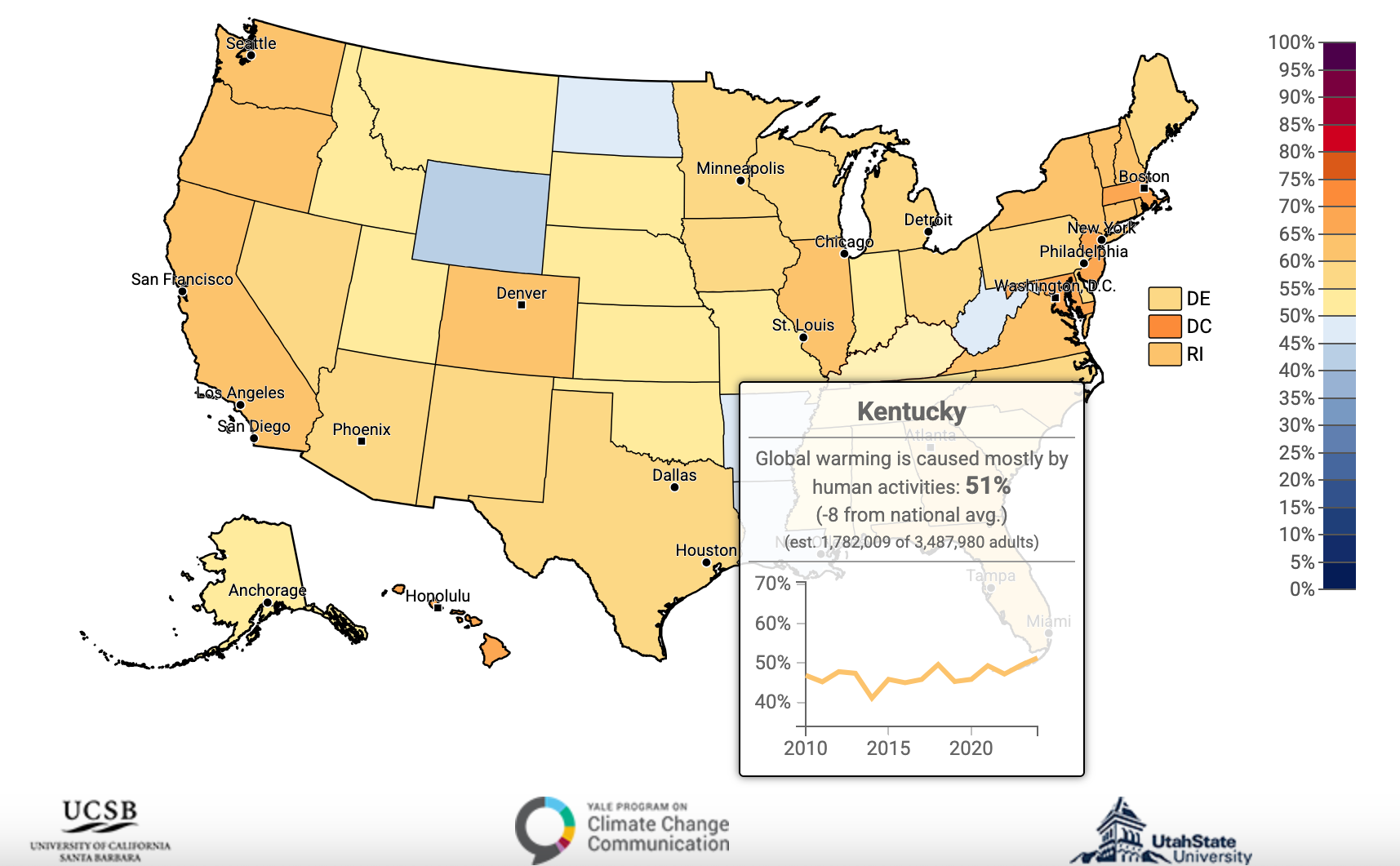

About 58% of the Lexington-Fayette Metropolitan Statistical Area is worried about climate change, according to a YALE Climate Communications report monitoring adults’ beliefs, risk perceptions and policy support around climate change. Likewise, 63% of Kentuckians surveyed expressed their belief that global warming exists.

“Kentucky tends to sit right about 10% below the national average, but it's not this dramatic swing. The national average is 72, so [people assume] Kentucky must be way down in the 30s.”

And the state’s urban centers, Lexington and Louisville, don’t dramatically drive up that number, she notes. The majority of people in every Kentucky county surveyed believe global warming is happening.

The YALE report doesn’t limit itself to the binary of people either believing or not believing in climate change itself, Cagle adds: Many people don’t center climate action in their lifestyles, but they’re still cautious or concerned.

“In our mental models of discourse around climate, we tend to sort people into the extremes– you're either alarmed, or you're dismissive … the folks who are like, ‘climate change is a hoax, I don't think it's happening at all,’” Cagle explains. It’s rarely so black and white.

“The reality is that people sit all along that spectrum. So just because someone is not a climate activist doesn't mean that they don't think climate change is real.”

The Central Kentucky Climate Action Plans challenge the idea that climate change is a rural and urban divide problem, Cagle says. These areas may have different needs, but most rural towns are not moving backwards compared to cities.

“As public opinion shifts further and further in favor of taking action on climate change across all spaces, urban and rural … there's increased public support for making systemic changes that will make it easier for individuals to make choices that reduce their own emissions,” Cagle argues.

Shanda Cecil wears many hats for the small city of Winchester, one county east of Lexington: She is its stormwater and floodplain coordinator, its code enforcement officer, and a correspondent for the Central Kentucky Climate Action Plan.

Cecil has been pushing for climate-forward initiatives in her community for years, from environmentally friendly practices in the local school system to Clark County’s farmland preservation and protection plan. These scopes differ from the rooftop solar and electric bus capabilities Lexington is shooting for.

“Every county seems to have similar goals, but the way we go about it does seem to be different,” Cecil explains. “Our viewpoints around things are slightly different. I am usually very practical about approaches, so I always try to grab the low hanging fruit first.”

Her current focus is on the school system, which she has gotten to know well since becoming an environmental educator. Cecil says she is meeting with other local leaders to implement composting for wasted school lunches and work toward eliminating non-recyclable styrofoam lunch trays.

“I've tried in the past to get that changed, and with not a lot of success, but maybe the composting aspect might actually happen if we can get a grant [to] create a facility on site to help compost,” Cecil says. “Food waste is 30% of the waste stream.”

In the draft Comprehensive Climate Action Plan, composting measures are projected to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by more than 300,000 metric tons regionally by 2050.

Many parts of the plan are oriented for the regional governments themselves to take on, but others – like recycling, reducing food waste and vehicle use – are based on individual habits changing. It also includes putting together public resources like the simple explanations of greenhouse gasses and climate change on the Climate Action Plan’s website.

“We're putting together educational materials about recycling … in a way that I can forward it to the other communities so that they can put it on their website, and they can get it out to their residents,” Griggs says.

“This is not a perfect plan, but it is a plan that [means] anyone should be able to pick up and do something, regardless of what type of home you're in, what size your business is – you can do something.”

Cecil, meanwhile, has grown more pessimistic about how much education can help drive change.

“I have been doing environmental education for about 23 years and I can tell you that it's not that people don't know,” Cecil says. The most difficult part of her work is getting people to act.

“It does not matter what political side you're on. I don't know why people don't make these changes. I am starting to believe they just don't care,” Cecil says. “I see people that will vote one way and, in their own personal life, do nothing to make a change.”

But she says this resistance has little to do with living in a more rural area.

“We're all getting our kids ready in the mornings. We're all going to work. We're all mowing our yards. We're all buying from Amazon.”