Council discusses ice storm gaps in city's winter weather response

Environmental Quality and Public Works Commissioner Nancy Albright said that the city was prepared for a normal snow event, not an ice storm.

Three musicians, born and raised states away, find themselves among family at a local bar every Monday night. They come for the music and stay for the community.

This story was produced as part of a joint Equitable Cities Reporting Fellowship for Rural-Urban Issues between CivicLex and Next City.

When Stephanie Duckworth first started baking pies, she brought one to her local old-time music jam – then at Lexington’s Broomwagon bike co-op – every week.

“That was my motivation to help me get better at pie baking,” she says. It was about being a good host for her fellow musicians, like she’d been raised to do in her rural hometown in eastern Tennessee. “'Cause I was making it for my friends, I always wanted to make it pretty.”

The weekly gathering first connected Duckworth with her now-husband, allowed her to meet numerous friends, and kickstarted her pie-making side business. It soon outgrew locations – and her baking, too.

“Eventually, it just got so big that I couldn't feasibly make enough pie for everybody.”

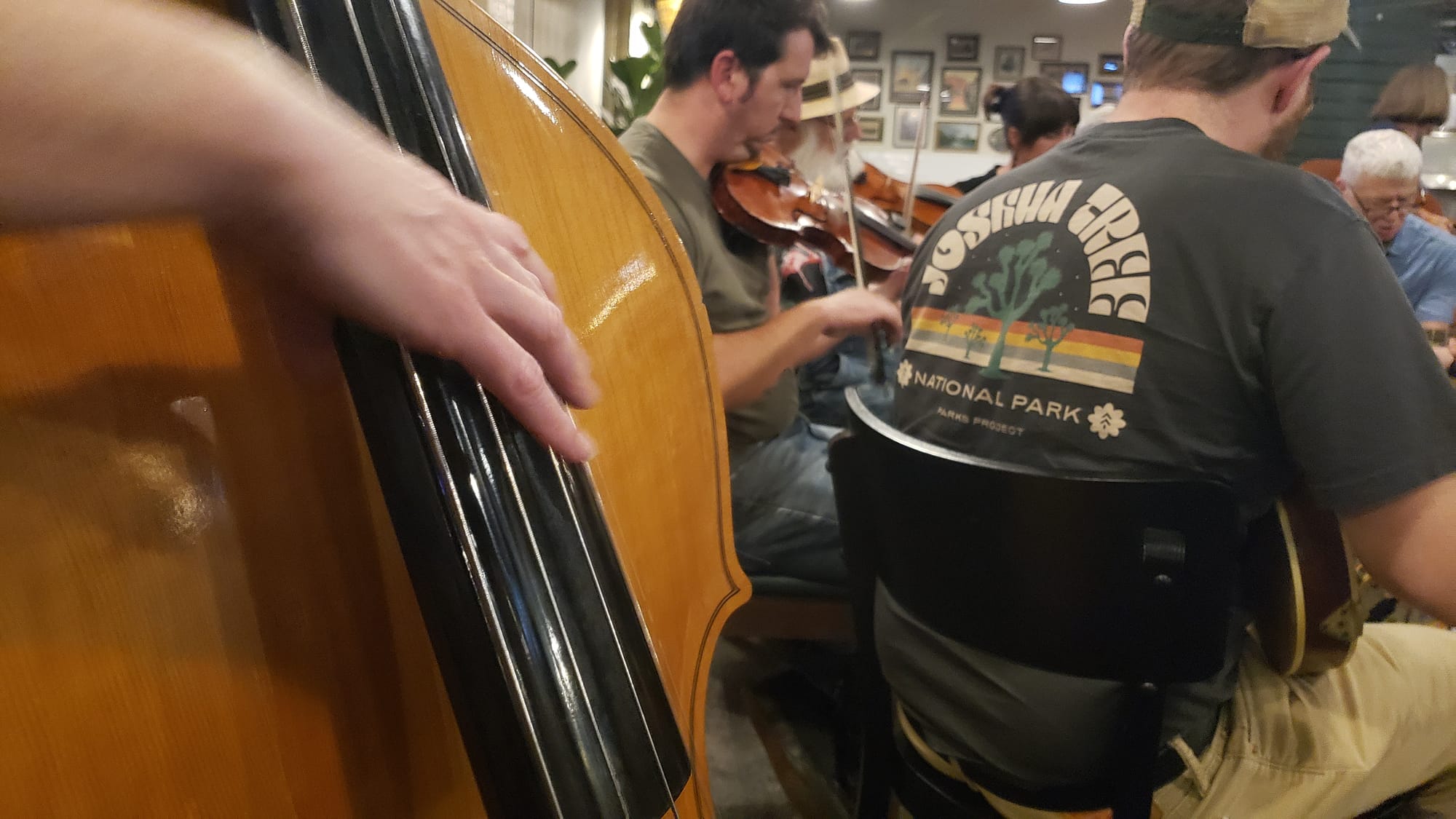

The old-time jam Duckworth helped lead now lives on at Old North Bar in Lexington, which hosts an old-time jam every Monday night at 6:30 p.m. and a ‘slow jam’ for new learners every Sunday. It’s not an official club where people sign up and pay dues, nor is it a concert where audience members get tickets and silence their cell phones to watch performers.

Instead, it’s a timeless way of building what researchers call social cohesion, or how people find belonging in their communities.

A “jam” is a gathering of multiple musicians together to play music in a relatively unstructured way. In Appalachian music, that’s usually through acoustic instruments: the fiddle or violin, banjo, guitar, mandolin and one upright bass. (Duckworth is usually stationed on the bass.)

Ultimately, the gathering is not about how it sounds, says Ron Pen, who helps organize the Old North Bar jam week after week.

“This is about the jam itself,” says Pen, a University of Kentucky music professor and ethnomusicologist focused on the Appalachian region. “It's active participation in music, and not passive consumption.”

Across the world, music is recognized as a powerful vehicle for social and cultural change. Old-time jams are a prime example in this region. For newcomers to Lexington, jams have proven an effective way to immerse oneself in a new community and build relationships – with people, businesses, and the state’s Appalachian culture.

Old-time music stems from Appalachian areas like her hometown, but Duckworth didn’t grow up playing folk music.

Duckworth describes the old-time jam as a constantly transforming gathering. She’s a core and founding member, but Duckworth hesitates to call herself an official organizational leader.

“We just showed up every Monday and helped keep the group together,” Duckworth says. “It’s hard not playing a melody instrument, not playing the fiddle, to effectively lead a jam. But there were enough people that came that played fiddle that felt comfortable leading the tunes.”

Duckworth grew up in a rural part of eastern Tennessee. Old-time music stems from Appalachian areas like her hometown, but the art form is only one reason why jams feel so familiar.

“You want to try to nurture the people that are there. It's almost like welcoming somebody into your home, when you're welcoming someone into a jam,” Duckworth says. “That seems like a very southern rural thing to try to do, at least from my upbringing … when they leave, make them feel better than when they came.”

Jams are an intentional way of forming community. In rural towns and areas, where the population density stays low, Duckworth says intentional gatherings keep people connected.

“If you had a big family and your family was tight, then of course you had that. I didn't have that; a lot of people from where I'm from did not have huge families,” Duckworth explains. “So, it's either you have clubs and organizations for school, or the church. So I think people are going to try to find community wherever they can.”

Not every rural Appalachian community has a thriving jam to call its own- hers didn’t, and she didn’t grow up playing folk music. Duckworth stuck around East Tennessee for the first 22 years of her life before venturing out as far as New York City to pursue classical music. Then, she got entangled in traditional genres like Bluegrass (a close relative to old-time music). Lexington is a relatively new spot for her.

But it soon became home– in these old-time jams, she met her now-husband and various friends. She no longer hosts; that role has been passed around casually since the gatherings began. Between her career as a physical therapist, her growing pie business, and other regular music gigs, there isn’t always time on a given Monday night.

Still, when she walks in the Old North Bar, people wave, and she slots right in the circle. Jammers bring birthday cakes and share in conversation no matter how much time has passed.

“Old-time music is about song and dance and food,” Duckworth says. “So much more than just notes and instruments. I think it just lends itself naturally to building a community, when it's in the right hands.”

Duckworth says like any community, there is unwritten etiquette to a jam. Give people equal attention, don’t make everything about yourself, and be courteous about how loud your instrument is.

“We have people that [bring] some percussion instruments, spoons, bones, different clackety type things. Sometimes those things can be very dominant.”

Bill Johnson jams anywhere he can: churches, festivals, wherever there are welcoming people to play with.

In Kentucky, there are plenty of options. He rattles off a list of old-time jams and events: Ohio Valley Gathering, Kentucky Music Week, Cowan Music School, Hindman Settlement School. “This part of the country, it's a real hotbed,” he says.

Johnson, who grew up in Kentucky’s rural Meade County, says jam settings are ingrained into the social fabric of the state and the entire Appalachian region.

“People would come and jam on the porch or find a church or some space where they can add dance to it,” he says. “And that was kind of a major part of the heritage of this Appalachian region.”

Active engagement within the music, Johnson says, is where he and many others feel the most at home – even when they might not fit in perfectly with the musicians around them.

The bluegrass (“three finger”) banjo he plays is different from the old-time banjo (also called “clawhammer” banjo) most prevalent at these jams, both due to the physical instrument and the techniques used to play. Bluegrass banjo is much more percussive and loud, bringing with it that dominance.

“I play that kind of banjo, and it's not always welcome at old time jams, in the purest old time [music],” Johnson says. “And that's fine.”

He has learned to play softly, he says, to make room for any other instrument. Even if his three-finger style isn’t congruent, he slides right in. He’s been doing it for decades.

As the fiddles kick off a new song, Bill points at the other end of the room, to a musician he’s known for a while.

“There's a lady over there. She's sitting back there with the dulcimer in her lap. Now, you can't even hear it over the fiddles and everything. But she comes and plays at almost every [jam],” Johnson says. “She's also started a dulcimer group and a dulcimer class here in Lexington.”

After all, he says, jamming is ultimately about the people.

“This stuff is more rooted in social interaction than it is performance anyway. And that's one of the beautiful things about it.”

Play, not academics

At the Old North Bar, Pen sits with his five-string fiddle, watching over as the night shapes itself. The people gathered here play for the sake of it.

“It's all just playing,” Pen says. “I don't use the word rehearse or practice ever with people when I’m talking about it. The semantics are important: what we're doing is playing. It's play.”

Pen is from Chicago, though he has strong Kentucky ties. He picked up the violin more than 50 years ago, starting classical and eventually earning his doctorate in musicology. Old-time jams, Pen says, transformed the way he viewed music. Once, this revelation came at a pig roast in Virginia.

“Everybody brought something to eat and shared it, and everyone either played music or square danced, and there was no audience,” Pen says. “I had been part of this art-music scene where you have people on the stage and people in the audience. I wanted to break that down in my life.”

Aside from arriving early and keeping the jam steady through the night, Pen also posts events in the jam’s public Facebook group, complete with narrative recaps of the past week’s fun.

“There were twenty-eight musicianers gathered in the strangely elongated egg-shaped oval this past Monday,” Pen wrote. “Moments of note included Robin's birthday and the revealing and signing of Steve's painting of the jam that was beautifully reproduced on canvas and framed by Cliff. Many thanks to all that brought this into reality.”

He’s also given presentations on the phenomenon, in a powerpoint he’s titled “The Anatomy of a Jam.” The event’s history and growth all tie back to that community they’ve built together, he says.

Pen’s years of schooling built his technical skill, but he adds there are many more ways to learn that don’t involve a stage or grades. One of these is the newer ‘slow jam’ every Sunday afternoon, where musicians young and old learn songs at a beginner’s pace. That way, participants can feel more comfortable going to the Monday jam afterwards.

Sure, people can now learn these tunes from the internet or a private tutor, he says. But going that route misses an important element of the music.

“[It omits] the context of the music and the stories associated with it – and from the people who live very rich and full lives,” Pen says. “For me, that's what the heart of this music was: those experiences I've had with people over the years, in their homes, sharing music around moonshine, working in gardens with them and hearing all the stories and where that tune came from.”